‘There is no peace here’: Colombia’s ethnic communities search for promised peace

By Atticus Ballesteros

colombiareports.com

Dozens of international human rights organizations published an open letter to President Juan Manuel Santos Tuesday, calling on Colombia’s leader to deliver peace to Afrodescendant and indigenous communities.

In a press release, the organizations behind the letter said the request comes in “response to a call for support” from ethnic communities in Colombia

Many of these communities live in the country’s Pacific and Amazonian regions where armed groups are vying for territorial control after the demobilization of the country’s largest guerrilla group, the FARC.

“Since the peace accord took effect late last year,” the organizations write, “Afro-Colombian and indigenous [communities] have witnessed an increase in human rights violations, including displacement.”

Many of these communities live in the country’s Pacific and Amazonian regions where armed groups are vying for territorial control after the demobilization of the country’s largest guerrilla group, the FARC.

“Since the peace accord took effect late last year,” the organizations write, “Afro-Colombian and indigenous [communities] have witnessed an increase in human rights violations, including displacement.”

Protecting Afro-Colombian and Indigenous Peoples’ territorial and other collective rights is fundamental to ensuring lasting peace in Colombia. Our survival as Peoples depends on the protection of these rights and our meaningful participation in peace implementation.

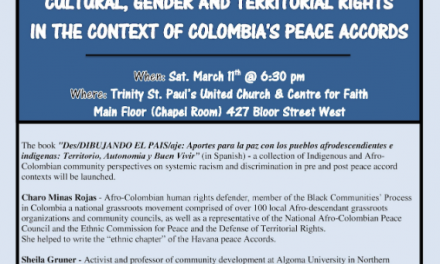

Charo Mina-Rojas (Black Communities’Process)

Leaders in ethnic communities in Colombia affirm that the situation on the ground is dire. They say FARC dissident groups, those rebels who abandoned the peace process, are responsible for much of the violence against ethnic communities. They also blame the government for failing to adequately take on the criminal groups.

“There is no peace here,” Fredy Lopez, a social leader in Colombia’s port city Buenaventura, told Colombia Reports.

There will be no peace until the national government, as the international community has demanded, resolves the problems it has promised to fix.

Buenaventura social leader Fredy Lopez

For Lopez, that means improving the security situation for ethnic communities around the country.

Since the FARC began the process of laying down their weapons and reintegrating into society earlier this year, certain sectors of Colombian society, especially in areas near FARC demobilization zones, have reported an increase in violence as other criminal groups compete for control over territory and abandoned criminal enterprises.

According to the Final Peace Accord with the FARC, the government was supposed to secure these areas while the FARC handed in their weapons.

Recently, the United Nations claimed the government’s fulfilling of its commitment to implement urgent peace policies has been “deficient.”

Colombia’s Ombudsman has also questioned the government’s commitment to security. The Ombudsman released a report Tuesday criticizing government efforts to secure areas previously controlled by the FARC, many of which are inhabited by majority black and indigenous peoples.

In a territory where we have the richest natural water sources in the country, but water only comes for two hours a day. In a territory where there is no hospital and they send people to their homes to die. In a territory where they kill, burn, and threaten our community because they need our land for industry. In a territory where many go to bed hungry, there is no peace here.

Fredy Lopez

Officials from the national government could not be reached for comment on the Ombudsman report or the letter signed by international organizations.

Over 150 organizations and individuals signed the letter to the Colombian head of state, including entities from the Congo, Canada, Mexico, Colombia, Norway, and the United States.

Some of the major signatories include the Colombia-based Black Communities’ Process (PCN), the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), distinguished Colombian academic Arturo Escobar, and even the Canadian Union of Postal Workers.