Overthrowing (Brazilian President) Dilma Rousseff

It’s Class War, and Their Class is Winning

By Alfredo Saad Filho

The Bullet

Every so often, the bourgeois political system runs into crisis. The machinery of the state jams; the veils of consent are torn asunder and the tools of power appear disturbingly naked. Brazil is living through one of those moments: it is dreamland for social scientists; a nightmare for everyone else.

Dilma Rousseff was elected President in 2010, with a 56-44 percent majority against the right-wing neoliberal PSDB (Brazilian Social

Democratic Party) opposition candidate. She was re-elected four years later with a diminished yet convincing majority of 52-48 percent, or a majority of 3.5 million votes.

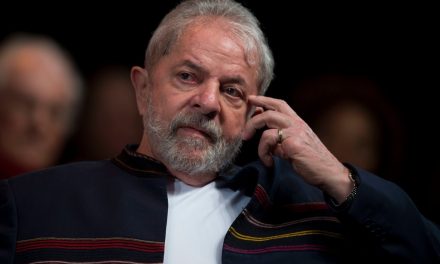

Dilma’s second victory sparked a heated panic among the neoliberal and U.S.-aligned opposition. The fourth consecutive election of a President affiliated to the centre-left PT (Workers’ Party) was bad news for the opposition, because it suggested that PT founder Luís Inácio Lula da Silva could return in 2018. Lula had been President between 2003 and 2010, and when he left office his approval ratings hit 90 percent, making him the most popular leader in Brazil’s history. This likely sequence suggested that the opposition could be out of federal office for a generation. The opposition immediately rejected the outcome of the vote. No credible complaints could be made, but no matter; it was resolved that Dilma Rousseff would be overthrown by any means necessary. To understand what happened next, we must return to 2011.

Booming Economy

Dilma inherited from Lula a booming economy. Alongside China and other middle-income countries, Brazil bounced back vigorously after the global crisis. GDP expanded by 7.5 percent in 2010, the fastest rate in decades, and Lula’s hybrid neoliberal-neodevelopmental economic policies seemed to have hit the perfect balance: sufficiently orthodox to enjoy the confidence of large sections of the internal bourgeoisie, and heterodox enough to deliver the greatest redistribution of income and privilege in Brazil’s recorded history, thereby securing the support of the formal and informal working class. For example, the minimum wage rose by 70 percent and 21 million (mostly low-paid) jobs were created in the 2000s. Social provision increased significantly, including the world-famous Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer programme, and the government supported a dramatic expansion of higher education, including quotas for blacks and state school pupils. For the first time, the poor could access education as well as income and bank loans. They proceeded to study, earn and borrow, and to occupy spaces previously monopolized by the upper middle class: airports, shopping malls, banks, private health facilities and roads, that were clogged up by cheap cars purchased in 72 easy payments. The government coalition enjoyed a comfortable majority in a highly fragmented Congress, and Lula’s legendary political skills managed to keep most of the political elite on side.

Then everything started to go wrong. Dilma Rousseff was chosen by Lula as his successor. She was a steady pair of hands and a competent manager and enforcer. She was also the most left-wing President of Brazil since João Goulart, who was overthrown by a military coup in 1964. However, she had no political track record and, it would later become evident, lacked essential qualities for the job.